By Bratislav Stefanovic, Senior Insights Manager at EyeSee

Brand blocking has long been a go-to merchandising technique for brand managers looking to ensure their brand stands out on the shelves. Although it may not seem obvious, there are several challenging questions that need to be addressed when applying this technique:

- Is the brand’s portfolio broad enough so it would pay off, but not too broad to induce a paradox of choice?

- What is a wider shelf/category context: price thresholds, competitors, anchor points?

- Will brand blocking of certain brands support or disable category growth?

All these dilemmas arise from the fact that brand blocking is impactful on two different levels, brand growth, and category growth, and the key to success is to reconcile and align those two. To understand how to do that, we should first look at shoppers, brand managers, and category managers’ points of view separately.

Brand blocking impact on consumers

According to the Food Marketing Institute, a traditional supermarket has from 15.000 to 60.000 SKUs, or around 40.000 on average. This means that there are an enormously large number of stimuli “attacking” consumers from the shelf, so for their “defense”, they use all sorts of anchors not to feel lost. Sometimes that is a price, emotion, or a clearly communicated claim.

Simply put, in the overwhelmingly large and diverse rows of SKUs, things can get complicated, which nobody wants. Complexity leads to indecision, which could lead to walking away from categories and products.

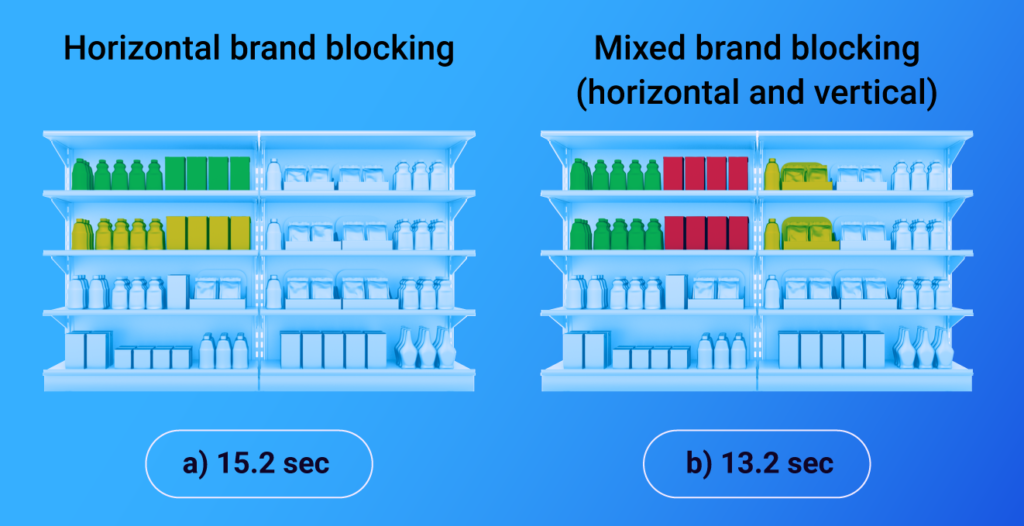

That is why blocking should help consumers scan through shelves, allowing natural browsing patterns like book reading. It is believed that horizontal blocking makes them spend more time browsing, noticing new SKUs and smaller brands, while vertical blocking ensures loyalty and decreases switching behavior.

However, in a recent EyeSee study, it was proven that horizontal brand blocking of one brand, which at the same time utilizes vertical brand blocking of its subcategories, can result in a visible increase in sales.

With the speed of the “shelf scanning” cut for 2 seconds, that methodology provided 32% of sales growth. However, while this type of blocking prevents price comparisons with potentially cheaper competitors, if not placed wisely, it could experience potential cannibalization. And this leads us to a question of the brand manager’s point of view.

Is brand blocking really a must for all brands?

Brand blocking for brands looks like a no-brainer: the product is clearly visible from afar, it takes up more space, and more importantly, it covers a larger surface in the consumer’s field of view.

The whole brand portfolio should come from the same key visual that allows brand creativity to emerge. Aside from the lead color scheme, they use visual connectors, some kind of characteristic design detail that connects the group of products: a logo, a circle with the claim, a line, or even the illustration of a cat on the box of milk, whose figure is complete when we look at the product facings.

Heineken has its famous red star, and Coca-Cola has its characteristic typography with an underlying lineage.

Pack tests in a realistic shelf setting can and should be used to determine whether the pack is outstanding enough, has a clear claim, and has a strong point of difference in comparison to competitors.

However, the impact of design is not the only thing that is relevant to shoppers. Price, or value for money, plays an important role as well. For example, if we put a large pack of products from the same brand next to or close to a smaller but premium pack and they have the same or similar prices, shoppers will compare those two segments of the same brand portfolio and will use the “cheaper” one as a threshold. In this case, brand blocking can be counterproductive unless Decision Three testing is used, which can help brand managers understand the role of every product in their portfolio and how it serves different target groups.

The category manager’s role in brand blocking

By using Decision Tree or Conjoint testing, category managers can get answers on whether it is the strength of the brand or price that will influence the shopper’s purchase, but in order to find an optimal solution, that will not be the only aspect they have to integrate into their decision making. For category managers, category growth is, understandably, their top priority, and brand blocking can both help and sometimes stand in the way of that growth.

Brand blocking helps in the case when:

- brand’s strengths help consumers identify certain subcategories or segments, such as health or occasion-based ones

- brand is a category leader and a strong driver of innovation and change

- brand assortments, or planograms, are already made with a category growth mindset

On the other hand, they must pay attention to the following:

- brand blocking by brands that do not innovate, or change can lead to status-quo and the fallout of both brand volume and category

- brand blocking can decrease the time that consumers spend shopping – they make decisions before coming to the store, disabling impulsive shopping on POS, which results in a smaller number of SKUs in their basket, which has a negative impact on category growth.

- brand blocking isn’t fit for brands that have too narrow brand portfolios; it simply doesn’t pay off.

Conclusion

When we examine brand blocking from three different angles: consumers, brand managers, and category managers, finding the perfect category planogram is more like solving a Rubik’s cube than painting a nice, branded color scheme on the shelves.

However, it is critical to remember that both brands and retailers want the same thing: for products to move and large-volume sales to occur. To be successful, the brands’ growth visions must align with the growth mindset of the category, and vice versa. This necessitates constantly looking at the big picture and making a series of informed decisions supported by data-driven insights provided by a series of context tests of shopper behavior in realistic environments.

Interested in category management? Check out our latest Deep dive podcast episode with the Clorox Company Insights Lead.